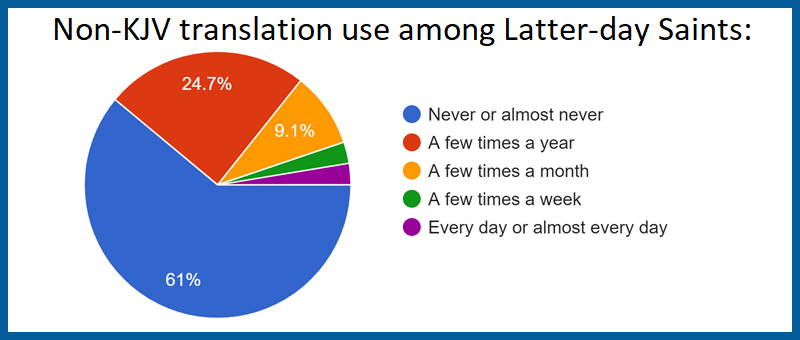

Note: This post is accompanied by my post “Data: Use of Modern (Non-KJV) Bible Translations among Latter-day Saints.”

Why is the King James Version (KJV) the official English version of the Bible used by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, even though it was created back in 1611? What are its advantages? What are the advantages of supplementing it with a more modern translation? If so, which should you use?

This article will address all these questions. But first, we need to explore two concepts at the heart of biblical translation issues:

Textual Criticism

No “original” or “perfect” manuscript survives of any biblical book. What have survived are thousands of Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic manuscripts (most of them fragmentary) from the late classical period and the medieval period (100 BC–1100 AD). These are copies of copies dating centuries or even millennia after the originals were written.

And here’s the problem: no two surviving manuscripts are identical. Whether due to scribal errors, editorial changes, or deliberate tampering, thousands of tiny (or large) variations exist in the corpus of manuscripts for any given biblical book.

A branch of scholarship called textual criticism deals with painstakingly comparing these manuscripts, tracking the discrepancies in letters and words, and deciding which variant is more likely to reflect the original. Translators then consult these textual critical studies to decide how to render passages that have alternate readings.

For example, was Goliath “six cubits and a span” (9–9 ½ feet) tall, as the medieval Hebrew Masoretic manuscripts read? Or was he “four cubits and a span” (6 ½–7 feet) tall, as the Greek Septuagint manuscripts and a Dead Sea Scrolls manuscript read?

Each decade, more ancient manuscripts are discovered, analyzed, and published (most notably the Dead Sea Scrolls in the late 1940s), meaning that the newer an English translation is, the more textual criticism it can draw upon, and therefore the more accurately it can present the original form of the text.

Formal vs. Dynamic Equivalence

Translating from one language to another is never a simple process of finding one-to-one correspondence in vocabulary (as much as Google Translate thinks otherwise). There are differences in grammar, word order, nuances, connotations, idioms, and expressions that all must be considered.

Translations fall on a spectrum from being formally equivalent (trying to render the literal word-to-word meaning as faithfully as possible) to dynamically equivalent (trying to render the overall sense as coherently as possible). A translation trying to straddle the middle is called an optimally equivalent translation.

The value of a more dynamically equivalent translation is it’s more coherent and understandable in the target language. The value of a more formally equivalent translation is it better preserves the nuance and subtleties of the original language.

As an illustration, compare these three translations of Isaiah 49:23:

|

Formally Equivalent Translation |

Optimally Equivalent Translation |

Dynamically Equivalent Translation |

|

King James Version (KJV) |

New English Translation (NET) |

Good News Translation (GNT) |

| And kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers: they shall bow down to thee with their face toward the earth, and lick up the dust of thy feet. | Kings will be your children’s guardians; their princesses will nurse your children. With their faces to the ground they will bow down to you, and they will lick the dirt on your feet. | Kings will be like fathers to you; queens will be like mothers. They will bow low before you and honor you; they will humbly show their respect for you. |

Surely to a child or to someone unversed in biblical language, the phrase “humbly show their respect for you” is much more understandable than the phrase “lick up the dust of thy feet.” But it is also less vivid, and it severely waters down the dramatic imagery that Isaiah is crafting.

The methodology of translation also can affect doctrinal meaning. By necessity, any act of translation involves interpretation. But the more dynamically equivalent the translation, the more interpretation is involved and the more the translator’s bias and theological outlook can creep into the meaning (intentionally or unintentionally).

Advantages of the King James Version

With this background, let’s explore the principle reasons the King James Version continues to be (in both my opinion and the opinion of Church leaders) the best translation for general Latter-day Saint use:

- KJV language is the language of restoration scripture. In the early 1800s, the King James Version was practically the only English translation in common use. So when the Lord revealed to Joseph Smith the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and other scripture, He employed King James language and phraseology, and quotes of biblical texts followed the KJV. By using the KJV in our studies, we are in a better position to compare language across scriptural books and identify intertextual references (such as when D&C 121:38 uses the phrase “kick against the pricks” to allude to Paul’s conversion in Acts 9:5).

- The KJV is the base text of the JST. Joseph Smith’s inspired emendations were layered on top of the King James text. Trying to map these changes onto a different translation would pose a complex challenge.

- Key doctrinal terms are drawn from KJV language. Phrases from the KJV such as “celestial,” “first estate,” and “dispensation of the fulness of times” (Ephesians 1:10) have come to take on special doctrinal significance in our theology. If we switched to a modern translation that employs different language in these passages, we would miss the connections between the Bible and these core doctrines.

- The KJV is highly literal. Of all the translations in widespread use today, the King James is the most formally equivalent, and therefore the least likely to be affected by translators’ doctrinal biases.

- The KJV is a poetic and literary masterpiece. Its effect on the development of English has been profound, and few modern translations can match its cadence and rhythm. Many readers also prefer its “thee’s” and “thou’s” and archaic verbal endings to modern vernacular, as they can bestow a sense of ancientness or holiness to the text.

Disadvantages of the King James Version

That said, the King James Version is by no means a perfect translation. Here are some of its principle downsides:

- Archaic language. English has changed a lot in 400 years. No one uses “thee” and “thou” in everyday parlance, nor fancy words such as “nevertheless,” “behold,” or “lest.” To those unversed in King James English, the language of the KJV poses a serious stumbling block to understanding the biblical text.

- Misleading vocabulary. Some words or phrases in English have changed meaning since the KJV was made, leading to misunderstandings. For example, in Jude 1:22 (“And of some have compassion, making a difference”), the phrase “making a difference” meant “differentiating” or “distinction” in 1611, but now is commonly misread as “making an impact.”

- Outdated scholarship. Scholars understand Hebrew and Greek grammar and vocabulary a lot better now than they did 400 years ago. In the previous example, most modern translations render the Greek verb διακρινομένους (KJV: “to make a difference”) with one of the verb’s alternate meanings, “to doubt” or “to waver.” Thus the NET: “And have mercy on those who waver,” or the NIV: “Be merciful to those who doubt.”

- Outdated textual criticism. The KJV translators had access only to very late Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. Numerous discoveries since then mean that newer translations better reflect the original text. For example, in Genesis 4:8, the Hebrew manuscripts available in 1611 read, “And Cain said to Abel his brother, and it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother, and slew him.” Did you notice the sentence fragment? The KJV translators patched over this by rendering the first phrase, “And Cain talked with Abel his brother.” But since then, textual critics have noticed that the Septuagint (ancient Greek translation), Vulgate (ancient Latin translation) and ancient Syriac manuscripts all supply the missing phrase: “And Cain said to Abel his brother, ‘Let us go out to the field.’ And it came to pass, when they were in the field . . .”

Benefits of Supplementing the KJV with Modern Translations

For the serious student of the Bible, there are many benefits to using a newer translation (or two) to supplement the KJV in your personal or family study—especially if the newer translation is a “study bible” edition, with notes, commentary, and background information. Here are the principal advantages:

Textual Reasons

- More understandable: Modern translations employ modern English vocabulary, grammar, syntax, and spelling, making the scriptures more understandable.

- Higher quality translation: Modern translations often are more accurate than the KJV in how they translate tricky grammatical constructions or rare vocabulary terms.

- Better textual criticism: Modern translations are based on older, more accurate Hebrew and Greek manuscripts.

Formatting

- Paragraph divisions: Most modern translations divide the text into paragraphs of several verses each, instead of individual verses. Since ideas most often run on from verse to verse, the paragraph structure helps with comprehension. It also helps avoid “proof-texting,” the unhealthy practice of interpreting a verse without regard to the context of the verses preceding and following it.

- Poetic formatting: Much of the Old Testament and some of the New Testament is poetry. Most modern translations signal this by formatting the text by lines and stanzas, making it easier to (1) identify the text as poetic (and therefore read it as such), and (2) notice parallelisms, contrasts, and other poetic patterns.

- Section headings helping to clarify where one story or idea ends and another begins.

- Quotations marks signaling dialogue or quotations.

Study Aids (found in most study Bible editions)

- Translational notes giving possible alternate meanings of words or phrases, noting significant textual variants, or explaining the nuances of particular words.

- Interpretive notes explaining geographic, cultural, or theological context, or restating or summarizing the idea in a simpler way.

- Commentary providing more interpretation and analysis. (Though be mindful of the theological bent of the commentators.)

- Cross-references to biblical passages that quote or are being quoted by the passage at hand. (For some study Bibles, these cross-references are more thorough than the footnotes in the Church’s edition of the KJV.)

What Are the Major Non-KJV Translations?

There are dozens of English translations, and exploring the different options can be dizzying. There are four main qualities that distinguish modern translations from each other:

- Where they fall on the spectrum of formal equivalence to dynamic equivalence.

- The reading level of the translation

- Whether they use gender-inclusive language or not (whether terms such as “men” and “brothers” in the Greek and Hebrew should be changed (when applicable) to “men and women,” “brothers and sisters,” etc.).

- The theological background of the translators (Jewish, Catholic, Evangelical, secular scholars, etc.)

Below is a quick guide to the most widely used translations. (Information drawn from William W. Klein, Craig L. Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard Jr, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, third edition, Zondervan, 2017, 192–197.)

Formally equivalent translations

- King James Version (KJV) – 1611. A highly literal translation made by a team of Protestant scholars and theologians. (Nearly all modern editions, including ours, reproduce a 1769 edition that updated the spelling and grammar.)

- New King James Version (NKJV) – 1982. The KJV with the most obsolete words and grammar updated.

- New American Standard Bible (NASB) – 1971. An evangelical-led revision of the American Standard Version, a revision of the KJV made in 1901. Strives to be very formally equivalent while using modern English.

- English Standard Version (ESV) – 2001. An Evangelical translation. Does not employ gender-inclusive language.

- New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) – 1990. An update of the 1952 Revised Standard Version, the first high-quality English translation drawing upon modern textual critical knowledge. Uses gender inclusive language. Very widely used, especially in ecumenical, nondenominational, and secular contexts.

Optimally equivalent translations

- New International Version (NIV) – 1978. An evangelical-led translation. Does not employ gender-inclusive language. Used very widely in evangelical circles.

- New International Reader’s Version (NIrV) – 1996. A version of the NIV geared for children and beginning readers.

- Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB) – 2004. Similar to the NIV, but employs gender-inclusive language.

- Common English Bible (CEB) – 2011. Strives to stay loyal to the original text while using contractions, colloquialisms, and other relaxed English usage.

- New English Translation (NET) – 2005. An inter-denominational translation sponsored by the Society of Biblical Literature. Most distinguished for the 60,932 translators’ notes in the online version, meant to lay bare the textual and translational decisions behind the translation.

- New American Bible (NAB) – 1970. One of the principal English translations used by Roman Catholics

Dynamically equivalent translations

- Good News Bible (GNB) – 1976, a highly paraphrastic translation published by the United Bible Society.

- New Living Translation (NLT) – 1996. A highly paraphrastic translation.

- Contemporary English Version (CEV) – 1995. Uses contemporary expressions and terminology.

- New Century Version (NCV) – Began as a popular children’s Bible later updated for general use. Strives to use very simple English.

So Which Translation Should I Use?

Here are my personal recommendations:

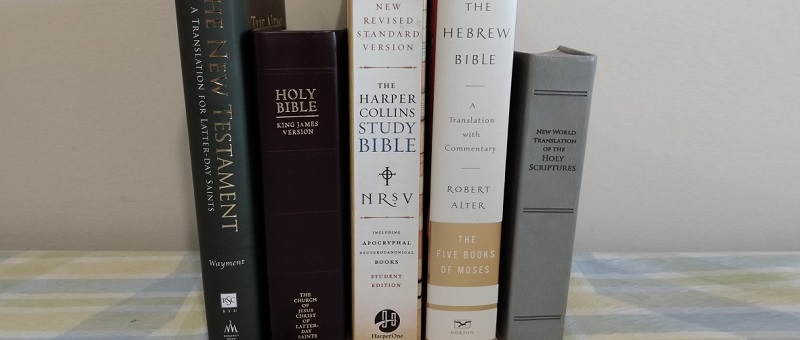

- If you want a formally equivalent translation that is similar to the KJV but easier to understand, use the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV). I enjoy the Harper Collins Study Bible edition of the NRSV.

- If you want a more optimally equivalent translation for easier reading, use the New International Version (NIV).

- If you want a translation that provides in-depth textual information and explanatory notes, use the online version of the New English Translation (netbible.org).

- If you want a dynamically equivalent translation of the New Testament by a BYU scholar with notes and cross references to the JST and other standard works, I highly recommend Thomas A. Wayment’s The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints—A Study Bible (Deseret Book, 2019).

Where Can I Find Them Online?

- The New English Translation (NET) has its own dedicated website: netbible.org. It also has a very good interlinear tool for comparing the English side-by-side with the Greek and Hebrew, with pop-up dictionary definitions for each Greek and Hebrew word.

- biblegateway.com provides access to dozens of translations, including the NIV and NRSV.

- biblehub.com is another good website with various translations, commentaries, and interlinear tools.

All three websites also have mobile app versions.

Summary

The King James Version is the official English translation used by the restored Church of Jesus Christ because it provides continuity with the language of the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, JST, and our theological terminology. However, its archaic English and outdated scholarship can impede understanding. There are numerous advantages to supplementing your personal or family study of the KJV with a modern translation such as the NRSV, NIV, or NET, especially if you select a study Bible edition with formatting, notes, and guides to aid understanding.

Further Reading

- “First Presidency Statement on the King James Version of the Bible,” Ensign, August 8, 1992.

- Franklin S. Gonzalez, “With so many English translations of the Bible that are easy to read, why does the Church still use the King James Version?,” Ensign, June 1987.

- Joshua M. Sears, “Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints,” Religious Educator 20 No. 3 (2019).

- Ronan James Head, “Unity and the King James Bible,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Summer 2012, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 45–58.

Wow! This is a very thorough post! I had never thought about the advantages of supplementing the King James Bible. You give some very good reasons doing so. Thank you!

Glad it was helpful!

Pingback: Data: Use of Modern (Non-KJV) Bible Translations among Latter-day Saints - Precepts of Power

Pingback: Which English Translations of the Bible are the Most Reliable or Preferable? | FINES ET INITIA